Truong Vinh Ky (born Truong Chanh Ky, also known as Petrus Ky) was likely the first Vietnamese scholar to be listed by the French Academy of Sciences among the world’s greatest scholars in the Larousse dictionary. He authored more than 100 works, transcribed The Tale of Kieu into the Romanized Vietnamese script (Quoc Ngu), and can be regarded as an early cultural ambassador of the Vietnamese people during the French colonial period.

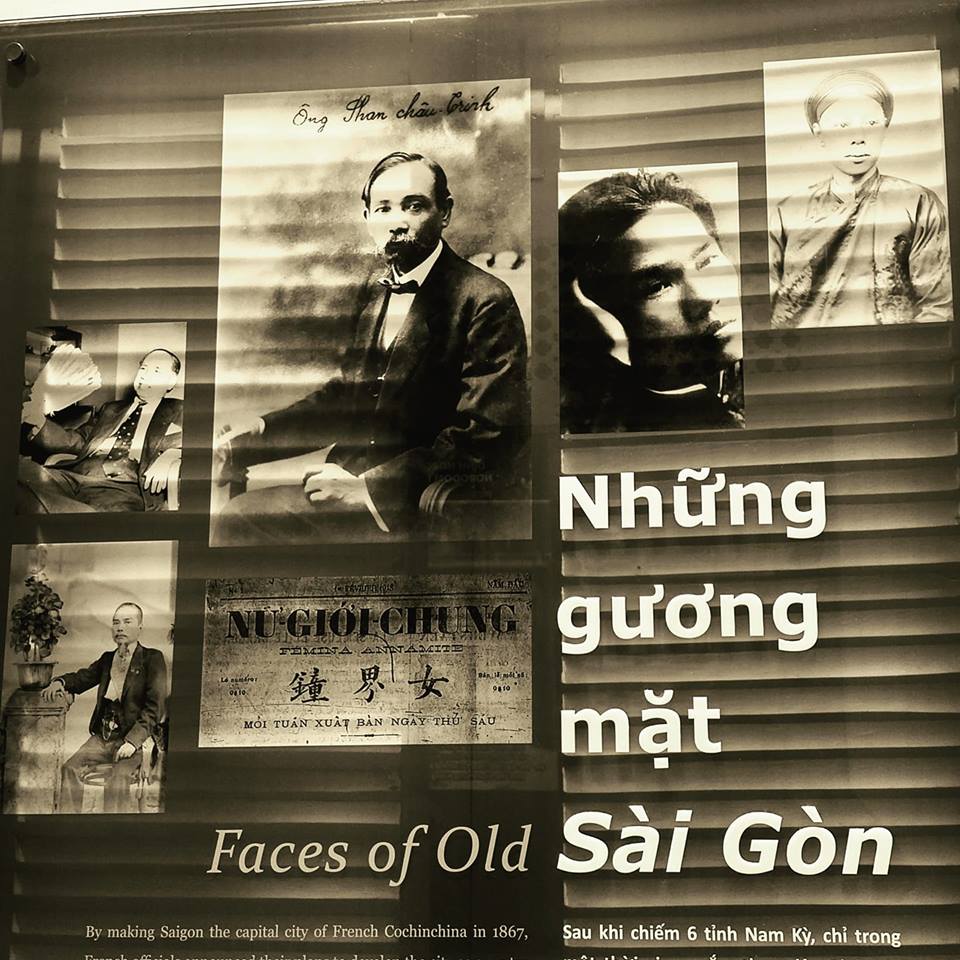

Phan Chau Trinh is perhaps the most renowned among the five figures presented here. He was a leader of the Duy Tan (Modernization) Movement and is considered the father of Vietnam’s non-violent struggle movement. His philosophy continues to be widely cited as a possible path for Vietnam’s development: Enhancing people’s knowledge, strengthening civic spirit, and improving livelihoods. When Nguyen Tat Thanh traveled to France, Hy Ma was the one who supported the young man at that time. When Phan Chau Trinh passed away, some 60,000 people in Saigon joined his funeral procession.

Nguyen An Ninh was a member of the “Five Dragons” group in France, together with Phan Chau Trinh, Phan Van Truong, Nguyen The Truyen, and Nguyen Tat Thanh. The group often shared the pen name “Nguyen the Patriot” (Nguyen Ai Quoc). After returning to Vietnam, Nguyen An Ninh became a patriotic journalist and even sold medicated balm to spread revolutionary ideas. He was also a symbol of non-violent resistance in old Saigon. His most famous poem begins with the lines: “Why live a useless life? / What is life worth without conscience?”

Do Huu Phuong, also known as Governor Phuong, was a wealthy Chinese-Vietnamese businessman. He was among those who helped shape and establish Saigon’s first girls’ school, later known as Ao Tim, Gia Long, and today Nguyen Thi Minh Khai High School.

Suong Nguyet Anh, the beloved daughter of Nguyen Dinh Chieu, was the editor-in-chief of Vietnam’s first newspaper dedicated to women’s rights. Many consider her to be the country’s first feminist.

Truong Van Ben was the wealthiest tycoon in Saigon. His most famous product was Co Ba Saigon soap, which became a cultural icon.

What surprised the author most is that these six figures are presented in an objective and non-hostile manner. Upon closer examination, five of the six individuals (with the exception of Suong Nguyet Anh) were at times criticized or considered taboo in official discourse after 1975. Petrus Ky was disparaged for having worked as an interpreter for the French, and for viewing leaders of the Can Vuong movement as outdated. Phan Chau Trinh was often portrayed in post-1975 history textbooks as reformist, and his legacy was never thoroughly studied. Nguyen An Ninh was associated with the origins of Trotskyism in Vietnam; one of his close associates, Ta Thu Thau, was assassinated for being a “Trotskyist” and later erased from public memory. Truong Van Ben was long ignored because he was a capitalist, while Do Huu Phuong was labeled “the most effective collaborator of the French” for participating in the suppression of uprisings led by Truong Quyen and Nguyen Trung Truc.

However, applying contemporary political bias to judge historical figures is inherently one-sided, as it risks either glorifying or demonizing individuals. A historical figure may be viewed as a villain by some and a hero by others, but historical scholarship must remain neutral. The perspective adopted by the ongoing exhibition truly follows this approach, which is both valuable and commendable—similar to how figures of the Republic of Vietnam period are presented on the second floor of the exhibition.

For more details about the exhibition, see

here.

Le Nguyen Duy Hau